Saving Juan Manuel Santos

On October 7th, 2016, the Nobel committee awarded Colombia’s el presidente, Juan Manuel Santos, the Nobel Peace Prize. It was only five days after the peace referendum in Colombia which was rejected by 50.2% of the valid vote. Having been underestimating the concerns of the “no” camp, Santos was criticized; some Colombian intellectuals even raised their voices and expected him to resign. Thanks to the Nobel Peace Prize, however, Santos comes out of the crisis stronger. He will most likely strengthen his hand against the leader of “no” campaign, former President Álvaro Uribe, as well as against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Now it is his turn to use his prestige and power to generate a more convincing agreement. In other words, the Nobel Prize will likely enable him to succeed in the second round.

Colombia has been under subversive civil war with the FARC for more than a half century; it did not seem possible to win the war militarily. There have been various attempts to end the longest and bloodiest civil war in the Western hemisphere, but none of them could ensure a sustained peace and stability. The Santos government initiated a peace process in September 2012 and has been negotiating for four years to end the civil war with the FARC. Many have supported the peace process; but there were also concerns questioning the justice of the agreement owing to the uncertainty of punishments and representation of FARC members in Congress.

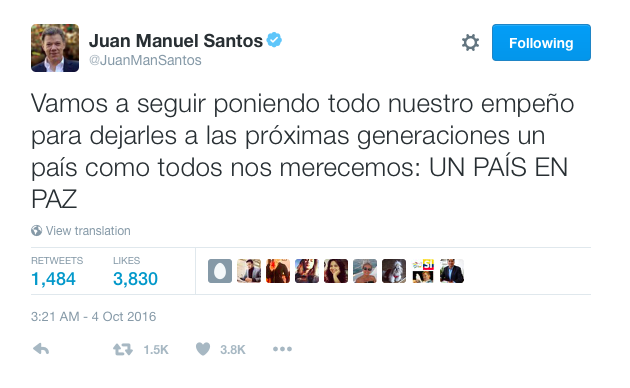

Significant number of surveys expected 60% or above “yes” votes for the peace agreement (For details, here). On October 2nd, however, Colombian voters vetoed the agreement by a narrow margin. Because of the lower turnout or the underestimation of the “no” camp, the result was an unpleasant surprise for the government. Daniel Raisbeck claimed that Santos “is in exactly the same position as Cameron after the vote that led to Brexit” (Here). The political context was about to enable Former President Álvaro Uribe to regain his political power to take his place in renegotiating the deal. It would likely to be an end to the Santos government. Santos did not give in; he declared, “We will continue putting all our efforts to pass on to future generations a country like we all deserve: A COUNTRY IN PEACE.” The good news is that FARC also seems to be committed to make peace. After the defeat at the polls, the rebel leader Timochenko said “We will continue to use words as our only weapons…Peace will triumph” (Here).

There are number of lessons that should be drawn from Colombian ongoing experience. In the national surveys, public support for the FARC is much less than 5% of the population; it does not have a democratic legitimacy though there might be an ideological one. The public veto further weakened its legitimacy. New agreement should involve more public satisfaction, as Javier Corrales and Daniel Altschuler wrote; “voters with relatively low levels of satisfaction can often behave recklessly at the polls”(Here).

Another lesson is that the role of international actors is undeniable. Yet the international aid does not necessarily mean material support. Especially in anti-imperialist contexts, substantial proportion of citizens would have difficulty understanding the intention of dominant powers and they are so cynical about foreign aid. In such contexts, non-material support is more effective. Verbal and moral support, how the Nobel Peace Prize functions for, is the source of legitimacy, prestige and pride. Sometimes promoting peace is just promoting peace.

Follow Ugur Altundal on Twitter: www.twitter.com/UgurAltundal

Originally published at Huffington Post on 10/08/2016. Available here!